Quite by an accident – as I seem to come across everything interesting nowadays – I found myself looking at pictures of old playing cards, and ran into the Flemish hunting deck, circa 1475. (Also known as the Cloisters deck, as it’s in the Cloisters Collection in New York. Oddly, the Cloisters website suggests that these cards are parodies of Burgundian court fashions: in fact, there’s nothing parodic about these costumes, unless all portraits and manuscript illuminations of this era are likewise parodies. . . )

I was immediately struck by how much one of the Queens – the Queen of the Hunting Horns, pictured above – looked like Elizabeth Woodville. Thanks to Tor Gjerde’s excellent website about old playing cards, I was able to zoom into the lady’s face, and by his permission, I’m using his scans of the reproduction deck in this post. Click on this link to see the deck in its entirety; you can click on each card to see the bigger version in full.

I have Googled and searched high and low, but nowhere did I find anyone else make the suggestion that the Queen above might be based on a portrait of Elizabeth Woodville. So, here I am, then: making that very suggestion.

The facial resemblance alone made me convinced this was Elizabeth, but on top of this her gown and headgear are both typical of English fashions of this time, and her underskirt of red and gold could be seen as referring to the heraldic colours of the crown of England. Most notably of all, of course, the lady is carrying a humongous white rose in her hand!

In the comparison collage below, I decided to include not only the best-known portrait of Elizabeth Woodville, but also a manuscript depiction that is contemporaneous with these cards, from the Luton Guild Book. (Please click on each collage to see the detailed version! The full-sized collages didn’t fit on this page.)

Comparing the King of the Horns with portraits of Edward IV is more difficult, as Edward had the knack of looking like a completely different person in all portrayals of him. The picture from the left is from the Luton Guild Book, whilst the picture on the right is a later copy of a portrait. But I can think of at least one manuscript depiction of Edward IV as a young man in which he had particularly full lips and bore more of a resemblance to this card. I’ve never seen that picture in circulation on the internet, so I’m going to scan it some other day.

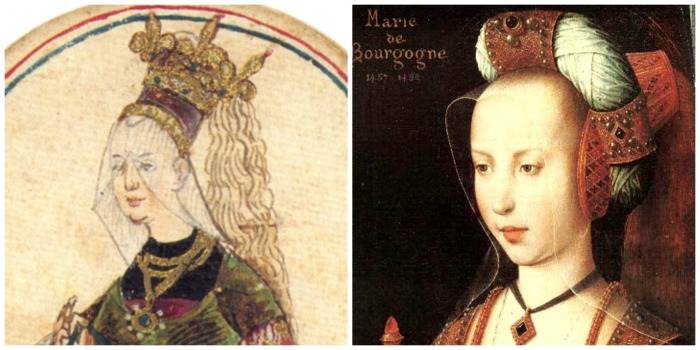

After thinking about these two, I also became curious about the rest of the figures on these cards. The Queen of the Tethers is a lady whose long hair cascades out of her truncated hennin, in a style that was popular among Burgundian young ladies at this time. (Or, as I also call her, ‘the Young Lady with the Atypically Large Bosom for Her Time Period’. This kind of attention to detail also makes me convinced that the creator of these cards had specific people in mind: compare this curvy young lady to the Queen of the Horns, who is fashionably slim, small-busted, and long-limbed.) She seems to bear a strong resemblance to Mary of Burgundy.

If the lady above is Mary of Burgundy, then surely the King of the Tethers would be her husband, the dashing young Archduke Maximilian. (Note the dragon spitting fire down his leg: I take this to be a reference to the Order of the Dragon, of the Holy Roman Empire.) There is no identified portrait of young Maximilian that I’m aware of, but below the card is compared with a portrait of a much older Maximilian, who was by then the Holy Roman Emperor himself.

(Mary and Maximilian married in the autumn of 1477, and Mary died in 1482 after a riding accident, so I’m guessing this deck of cards dates back to that short period of time.)

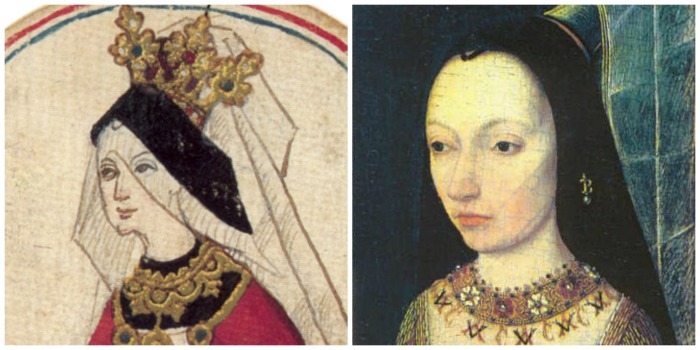

If the man above is Maximilian, then it would make sense for the older man with a long German-style beard to be his father Frederick III, the Holy Roman Emperor; and the lady with the German-style turban headdress to be Maximilian’s mother, Eleanor of Portugal, who had died in 1467. Frederick never remarried.

The comparison pictures in the collage below represent Frederick and Eleanor when they were younger (though painted posthumously), although I’m pretty sure I’ve seen a manuscript image of Frederick with a long beard somewhere.

The last couple, the King and Queen of the Dog Collars, are more difficult to identify, and of them I’m much less sure. At first I thought the lady looked a bit like a manuscript picture I’d once seen of Charlotte of Savoy, the wife of Louis XI of France; but considering the entire scheme of these cards and their seemingly inter-related houses, and the fact that the King of the Collars is the only one of these figures to wear armour, it would probably make more sense for it to be Mary’s father, Charles the Bold, who had died on the battlefield so recently, in the spring of 1477 – and who seemed to be quite fond of being depicted in armour. Indeed, these cards might have been a souvenir of Mary’s succession and marriage.

In that case the Queen of the Collars would either be Mary’s long-dead mother, Isabella of Bourbon, or Mary’s loving stepmother, Margaret of York: of the two, the latter would probably be more likely, as it would be closer in time and also fit in with Margaret’s brother Edward IV being included in the deck. Comparison pictures of Charles the Bold (as a much younger man, painted by Rogier van der Weyden in 1460; as well as a later portrait that may be posthumous or a copy of an original) and Margaret of York below.

Interestingly, the knaves – or knights – of this deck also have clearly differentiated facial features: but whether they’re meant to represent famous, recognisable figures is hard to know. All the three knaves or knights wear purple sleeves or pants, so that might imply that they’re closely associated with their respective royal houses. I made some comparisons and wrote down some speculation about these characters, but they were so purely speculative that I decided not to include them, so as not to make the identifications above seem less credible – as I believe them to be quite accurate.

But below are the knaves’ faces side by side, so you can see just how specific and detailed their facial features are.

***

If this deck of cards does indeed depict recognisable figures of real-life royalty, to me that raises the question: who were these cards meant for? Did the intended audience consist of higher-born people, who might be expected to recognise the likenesses of royalty, both domestic and foreign? Or were these cards sold as popular depictions of royalty, for ordinary people who were curious to know what their celebrities looked like?

This is something I’ve often wondered about, about this era: given that – for instance – manuscript illustrations range from extremely crude and generic to extremely accomplished and detailed, to what extent did common people (even the well-to-do ones amongst them) know what their rulers and other famous people looked like? How many of these popular depictions might there have been in circulation, in different ephemeral forms? It is through sheer luck that this deck of cards has survived, after all.

And the most fascinating idea of all: how many of such popular depictions might actually have survived, and be out there even as we speak – scattered all over Europe or beyond, still unidentified?

Credibility be damned, I’m going to write my speculation about the knaves’/knights’ identities anyway 😉 (I’ll call them knights, as the dashes of gold in their apparel denote high rank, and the purple might even imply royalty.)

I’ve got this theory that they might represent brothers to the kings of their respective houses. In this case, the knight of the nooses would be Frederick’s only brother Albrecht, Archduke of Austria, who was long dead by this time:

(Alternatively, it might be a time-travelling Martin Clunes. You never know.)

The knight of the collars could be Charles the Bold’s illegitimate older brother, Anthony, bastard of Burgundy, very famous in his time (and in his 50s by the 1470s, which would explain the somewhat greying hair on the card):

That leaves the knight of the hunting horns, who could be either Clarence or Richard. If the cards were made after February 1478, when Clarence was executed, that would leave only Richard. I do think there’s a certain resemblance between the young man on the card and the Society of Antiquaries portrait of Richard, though of course it’s hard to tell because the man on the card is blowing the hunting horn:

Who knows…?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Heavens, Dragonhound, you’ve done it again. I have so much to look at and think about with these cards. Thank you for the amazingly tantalising blog!

LikeLike

Why, thank you so much, Viscountess! I’m delighted that you enjoy it 🙂

LikeLike

Really interesting. When you said you weren’t going to try and id the last figures, I did in fact think ‘hunting horn’ might be Richard before I saw that you had indeed included him. I thought the first figure with the curlier hair and largish eyes might be Clarence

LikeLike

Thank you, hoodedman1 – glad to hear I’m not the only one to speculate about Mr Hunting Horn 🙂 I also find it interesting that the House of Tethers (my, that sounds very ‘official’) has no knight at all: obviously neither Mary nor Maximilian had siblings, so I wonder if that’s another clue that the knights might indeed represent brothers…

LikeLike

Another brilliant find! The white rose and Margaret’s crown clinch it, even if the physical similarities were not enough – and the similarities are quite striking!

I wonder if this means that the people who played with these cards had some idea how all those the royal “celebrities” of the day looked like (even if it’s by description), or if they were just recognizing most of the figures based on details, such as the white rose? Did the artist see any of these in person, or was he just going by portraits and descriptions?

I agree that the Knight of the Hunting Horns is most probably Richard, the nose and the chin are distinctive and look like him, much more so than George. Even the build fits how he’s speculated to have looked like, with long legs and comparatively short trunk (though the fool figure is similar, only with thinner legs). There is some subtle differentiation in the men’s build, though maybe not as obvious as with women, but I don’t know if it’s based on real appearances, or if it’s just to make the figures different; the knaves have stronger legs than the three kings (except the King of Horns/Edward, whose figure we don’t see due to his long cloak) and the fool. The three Kings’ build may be drawn as generic, but I couldn’t help but notice the rather muscular calves, especially compared to thin ankles and knees of the Knave of Hunting Horns (like someone with a gracile bone structure who’s however in a good athletic shape?), which reminds me of the figure in doublet from the picture of Jean de Wawrin presenting his manuscript to Edward IV, who has also been speculated to be Richard (though there’s been disagreement over that, and it’s also been said to be just a ‘stock figure’).

LikeLike

timetravellingbunny:

I wonder if this means that the people who played with these cards had some idea how all those the royal “celebrities” of the day looked like (even if it’s by description), or if they were just recognizing most of the figures based on details, such as the white rose? Did the artist see any of these in person, or was he just going by portraits and descriptions?

That’s what I’ve been wondering about, too. People tend to assume that the population of those times didn’t really know – or care – much about affairs beyond their own parish, but the fact is that we don’t know how widely portraits of this kind were circulated. Bourgeois culture was booming, especially in central towns, so it seems obvious to me that people would have enjoyed some ‘celebrity gossip’ as much as modern people do. My guessing is that ordinary people, or at least the ‘middle-class’ ones, would have been very curious to know what Kings and Queens looked like. And if there was a market for it, there would have been plenty of people to cater to that market: cheap miniature-painting was a big industry in the mid-to-late 15th century.

These cards definitely don’t look like they’ve been used much, and the quality of the portraits is really rather good, isn’t it? Perhaps they were more of a souvenir, or a status symbol; something to show to curious neighbours…

I agree about the build of the figures, too. Some curious, subtle differences there. I, too, would love to know whether the artist was drawing likenesses after portraits he (or she! there were accomplished women miniaturists as well) had seen, or whether s/he had even seen these people in life.

One possibility that occurred to me was that IF these cards were made in honour of Mary and Maximilian’s marriage, they might have been drawn from ‘official’ templates which in turn might have been drawn from life. Kind of like official royal wedding memorabilia these days: they serve a PR purpose as well as making some extra money.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Compare the Margaret of York card to her actual crown.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Doug – didn’t even occur to me! You’re right, it does look very similar indeed!

LikeLike

One of these I would say was co-incidence.

All of them? I think the chances are either astronomically small, or absolutely spot-on, and I’m not sure which.

Its certainly convincing and plausible, however.

LikeLike

Thank you, J.G. It is interesting to ponder, isn’t it?

(I love your replica work, by the way!)

LikeLike