I was reading this interesting summary of the case of Sir Roland de Velville/Veleville – who may or may not have been Henry VII’s illegitimate son – and thought of something.

Nowadays it seems be commonly assumed that ‘Velville’ was originally ‘Vieilleville’, and the only plausible Vieilleville family seems to be the Scépeaux family of Anjou, who were seigneurs of Vieilleville, and became comtes of Durtal in the 16th century.

However, the page above mentions that an early manuscript referred to ‘Roland de Bella Vill’. As I’ve been looking at French genealogy lately, ‘Bella Vill’ made me think of another family I’d noticed right in the middle of French and Breton politics – a family much better connected than the Scépeaux at this time period. The Bellevilles.

***

First things first: these Bellevilles actually started out as Harpedannes, and the Harpedannes started out as English Harpedons. (Possible alternative spellings: Harpden, Harpeden, Harpsden, Harpenden.)

Sir John Harpedon – apparently originating in Devon, if French genealogy sites are to be believed – is described in Nobiliaire et armorial de Bretagne as ‘connétable d’Angleterre, et capitaine général de l’armée anglaise en Guyenne‘, and the name does occur in Froissart as the seneschal of Bordeaux. Later on Sir John somehow became chambellan to Charles VI of France, and married the well-connected Jeanne de Clisson, heiress of Belleville through her mother. The mother Jeanne de Belleville was famous for her quest for revenge, and known as ‘the Breton tigress’.

The Harpedons inherited the Belleville lands as well as the title of the Belleville seigneurie in Poitou, and according to Histoire d’Olivier de Clisson, Connétable de France by Armand-Désiré de la Fontenelle, the Harpedon family wasted no time in changing their name to Belleville. The book emphasises that the original Harpedon name was promptly dropped; so even if the genealogical databases identify this family as (d’)Harpedanne de Belleville, it seems they only went by ‘de Belleville’ after this.

Jean II, the eldest son of John and Jeanne, is variously described as marrying either Jeanne d’Aspremont or Jeanne de Penthièvre, or both – both of which would have been advantageous marriages with well-connected families. Jean II’s son Jean III married Marguerite, the illegitimate daughter of Charles VI and his mistress Odette de Champdivers. Their eldest son Louis became councillor and chamberlain to Louis XI. By this time the Belleville clan was quite numerous and connected by marriage with a large number of powerful families in Brittany and France.

Not to mention, of course, that through their mother the children of Jean III and Marguerite were first cousins with Louis XI of France, Henry VI of England – and Edmund and Jasper Tudor.

(As an aside: Joseph Foster’s Dictionary of Heraldry mentions two different Harpden knights in the 14th century bearing, respectively, argent a mullet pierced gules; and argent on a mullet gules, a besant charged with a martlet sable. I don’t know if Sir John Harpedon came from a branch of this family or not, but either way, I’m guessing the Harpedanne-Belleville family’s coat of arms, ‘gironné de vair et de gueules de douze pièces‘, was the Belleville arms and was adopted with the name change.

I also don’t know what connection – if any – our Sir John Harpedon had to another Sir John Harpedon, who apparently married Joan de la Pole at some point and died in 1437/8; nor to this William Harpeden.)

***

Next let us look at the armorial evidence. This, too, is based on the description provided on the same page, which I suggest you read. There seems to be a lot of confusion as to what Roland’s coat of arms actually was like.

If Roland de Veleville was really Roland de Belleville, he doesn’t seem to have been a legitimate member of the family; at least, he doesn’t bear the Harpedenne/Belleville arms at all. Even if he were an acknowledged illegitimate son of a Belleville male, one would expect his coat of arms to reference the Belleville arms in some way.

(For what it’s worth, the Scépeaux/Vieilleville arms aren’t included or referenced at all, either.)

I’m not going to comment on all the different quarterings mentioned on the page I linked to. They might be Breton, they might be Welsh, and a person would go mad trying to hunt them down. (Believe me, I tried!) It’s impossible to guess anything without actually seeing the coat of arms in question. From the description, it is even unclear where exactly these different elements are placed on the coat of arms, or what the original sources were.

But the most interesting possible clue is in the prominent place that is, by all accounts, accorded to the argent, lion rampant gules. Apparently the contemporary Writhe has this as Roland’s personal coat of arms, and does not include the other elements at all. Is it, as the linked text suggests, the arms of the comtes of Poitou? Yes and no. In itself, the d’argent, au lion rampant de gueules is indeed the arms of the comtes of Poitou, which made me wonder about a possible connection to Charles VII of France, whose former mistress Antoinette de Maignelais had after all become the mistress of the Duke of Brittany. (And the Belleville family does have its close associations with the region of Poitou; but obviously one does not inherit a coat of arms that way.) But the other sources named in the linked text mention that the lion is crowned d’or. That makes all the difference. With the crown on top of the lion’s head – not merely on top of the entire coat of arms – it’s no longer Poitou, but Luxembourg-Ligny.

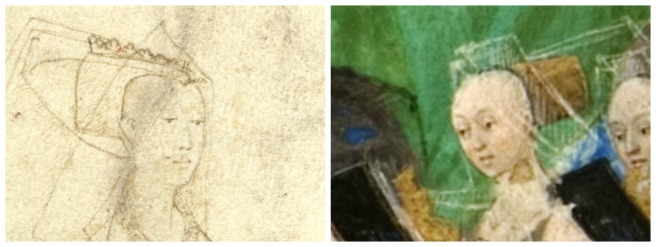

This is where it gets interesting: there was a Guillemette de Luxembourg-Ligny – daughter of Thibaud de Luxeumbourg-Ligny, comte de Brienne – who married Gilles de Belleville, the younger son of Jean III de Belleville above. The lion being marked with a bezant on the shoulder would also fit in with the Luxeumbourg-Ligny family; for instance, another cadet branch of Luxembourg-Lignys was differentiated with a cross or on the shoulder.

According to Père Anselme, Thibaud de Luxembourg-Ligny’s wife died in 1456, and he became a monk after her death; so Guillemette would have been born in 1456 at the very latest. She married Amé de Sarrebruche (or Sarrebruck), seigneur de Commercy, in 1463. She was apparently widowed in 1476, and then went on to marry her second husband, Gilles de Belleville, circa 1478.

The safest bet for the birth of a possible illegitimate son by Guillemette would therefore be this brief period of widowhood, circa 1476-78. Another possibility is that the son might have been born during her second marriage, which would explain the Belleville name, but that something (the date of conception, perhaps?) made it clear that the child couldn’t be her husband’s. (However, a birth date of 1478 or later would seem unlikely in light of Roland’s subsequent career: if Roland de Velville really participated in an expedition to Brittany in 1489, as is claimed, he can hardly have been a child of 11 or younger at the time.) At any rate, Roland certainly doesn’t appear as Gilles’ son anywhere, he doesn’t bear Gilles’ arms, and it seems hardly credible that Gilles – or any other well-connected nobleman, for that matter – would have shipped his own child off to England to live on the local King’s charity instead of marrying him into one of the powerful families back home.

Guillemette also had sisters, but this is where the unreliability of the available sources proves especially frustrating. Anselme tells us Louise, Hélène and Isabel became nuns, and Magdaleine (or Madeleine) married firstly in 1457 Charles de Sainte-Maure, and then in September 1485 Jacques Chabot, seigneur de Jarnac. But Charles de Sainte-Maure is also shown as having a second wife, Catherine d’Estouteville, with whom he had children from the late 1460s onwards – so I’m guessing he and Madeleine were married as children and the marriage was subsequently annulled. Besides annulment, there’s no explanation for them both living on to marry others, unless Anselme is confusing two different Madeleines with each other.

If Madeleine’s first marriage was annulled as a child, and she didn’t make her first proper marriage until September 1485, that’s unusually late for a woman’s first marriage in this time period. She would have been at least 28 by then; probably older. One is tempted to speculate what might have caused Madeleine to tarry until late 1485 before she finally married. Might she have hoped to marry somebody else, one wonders, before she realised it was never going to happen? If Roland were the son of Madeleine, the boy’s ‘Veleville’ name might have been an attempt to pass him off in England as a Belleville cousin. Doesn’t sound like an especially likely scenario – but then, stranger things have happened, and historical romance novels have been written on far weaker premises!

***

Historical romance or not, the Luxembourg-Lignys would actually have been good marriage material for Henry Tudor in the (early-to-mid) 1470s, assuming he (a) had no thought of aiming for the crown of England yet, and (b) wanted to return to England at some point.

You see, this is where it gets really interesting: Thibaud de Luxembourg-Ligny was Jacquetta Woodville’s full brother, thus making Guillemette, Madeleine and their siblings first cousins with the Woodvilles.

Such a close family relationship would have made a good first step towards reconciliation, don’t you think? At least until 1475, whilst Edward IV was still on good terms with Louis of Luxembourg.

Whether such a match was ever contemplated at all, but never happened because politics intervened, is anybody’s guess. But go on: I double-dare someone to write that speculative novel.

***

Whoever Roland de Veleville’s father was, I do think this Luxembourg/Belleville connection is a good starting point for finding his real mother. It has so many coincidences: the right location, the right-sounding name, the right(ish) age bracket, and the right coat of arms, too.