Quite by an accident – as I seem to come across everything interesting nowadays – I found myself looking at pictures of old playing cards, and ran into the Flemish hunting deck, circa 1475. (Also known as the Cloisters deck, as it’s in the Cloisters Collection in New York. Oddly, the Cloisters website suggests that these cards are parodies of Burgundian court fashions: in fact, there’s nothing parodic about these costumes, unless all portraits and manuscript illuminations of this era are likewise parodies. . . )

I was immediately struck by how much one of the Queens – the Queen of the Hunting Horns, pictured above – looked like Elizabeth Woodville. Thanks to Tor Gjerde’s excellent website about old playing cards, I was able to zoom into the lady’s face, and by his permission, I’m using his scans of the reproduction deck in this post. Click on this link to see the deck in its entirety; you can click on each card to see the bigger version in full.

I have Googled and searched high and low, but nowhere did I find anyone else make the suggestion that the Queen above might be based on a portrait of Elizabeth Woodville. So, here I am, then: making that very suggestion.

The facial resemblance alone made me convinced this was Elizabeth, but on top of this her gown and headgear are both typical of English fashions of this time, and her underskirt of red and gold could be seen as referring to the heraldic colours of the crown of England. Most notably of all, of course, the lady is carrying a humongous white rose in her hand!

In the comparison collage below, I decided to include not only the best-known portrait of Elizabeth Woodville, but also a manuscript depiction that is contemporaneous with these cards, from the Luton Guild Book. (Please click on each collage to see the detailed version! The full-sized collages didn’t fit on this page.)

Comparing the King of the Horns with portraits of Edward IV is more difficult, as Edward had the knack of looking like a completely different person in all portrayals of him. The picture from the left is from the Luton Guild Book, whilst the picture on the right is a later copy of a portrait. But I can think of at least one manuscript depiction of Edward IV as a young man in which he had particularly full lips and bore more of a resemblance to this card. I’ve never seen that picture in circulation on the internet, so I’m going to scan it some other day.

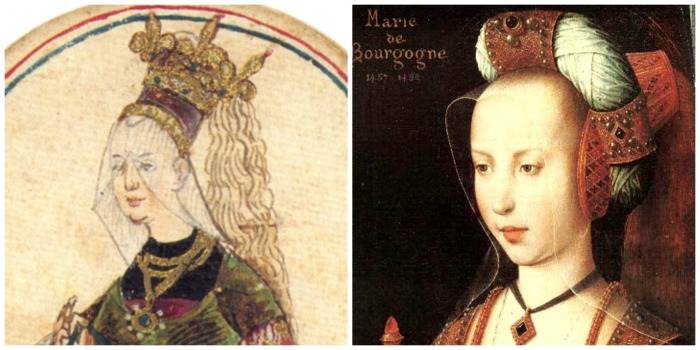

After thinking about these two, I also became curious about the rest of the figures on these cards. The Queen of the Tethers is a lady whose long hair cascades out of her truncated hennin, in a style that was popular among Burgundian young ladies at this time. (Or, as I also call her, ‘the Young Lady with the Atypically Large Bosom for Her Time Period’. This kind of attention to detail also makes me convinced that the creator of these cards had specific people in mind: compare this curvy young lady to the Queen of the Horns, who is fashionably slim, small-busted, and long-limbed.) She seems to bear a strong resemblance to Mary of Burgundy.

If the lady above is Mary of Burgundy, then surely the King of the Tethers would be her husband, the dashing young Archduke Maximilian. (Note the dragon spitting fire down his leg: I take this to be a reference to the Order of the Dragon, of the Holy Roman Empire.) There is no identified portrait of young Maximilian that I’m aware of, but below the card is compared with a portrait of a much older Maximilian, who was by then the Holy Roman Emperor himself.

(Mary and Maximilian married in the autumn of 1477, and Mary died in 1482 after a riding accident, so I’m guessing this deck of cards dates back to that short period of time.)

If the man above is Maximilian, then it would make sense for the older man with a long German-style beard to be his father Frederick III, the Holy Roman Emperor; and the lady with the German-style turban headdress to be Maximilian’s mother, Eleanor of Portugal, who had died in 1467. Frederick never remarried.

The comparison pictures in the collage below represent Frederick and Eleanor when they were younger (though painted posthumously), although I’m pretty sure I’ve seen a manuscript image of Frederick with a long beard somewhere.

The last couple, the King and Queen of the Dog Collars, are more difficult to identify, and of them I’m much less sure. At first I thought the lady looked a bit like a manuscript picture I’d once seen of Charlotte of Savoy, the wife of Louis XI of France; but considering the entire scheme of these cards and their seemingly inter-related houses, and the fact that the King of the Collars is the only one of these figures to wear armour, it would probably make more sense for it to be Mary’s father, Charles the Bold, who had died on the battlefield so recently, in the spring of 1477 – and who seemed to be quite fond of being depicted in armour. Indeed, these cards might have been a souvenir of Mary’s succession and marriage.

In that case the Queen of the Collars would either be Mary’s long-dead mother, Isabella of Bourbon, or Mary’s loving stepmother, Margaret of York: of the two, the latter would probably be more likely, as it would be closer in time and also fit in with Margaret’s brother Edward IV being included in the deck. Comparison pictures of Charles the Bold (as a much younger man, painted by Rogier van der Weyden in 1460; as well as a later portrait that may be posthumous or a copy of an original) and Margaret of York below.

Interestingly, the knaves – or knights – of this deck also have clearly differentiated facial features: but whether they’re meant to represent famous, recognisable figures is hard to know. All the three knaves or knights wear purple sleeves or pants, so that might imply that they’re closely associated with their respective royal houses. I made some comparisons and wrote down some speculation about these characters, but they were so purely speculative that I decided not to include them, so as not to make the identifications above seem less credible – as I believe them to be quite accurate.

But below are the knaves’ faces side by side, so you can see just how specific and detailed their facial features are.

***

If this deck of cards does indeed depict recognisable figures of real-life royalty, to me that raises the question: who were these cards meant for? Did the intended audience consist of higher-born people, who might be expected to recognise the likenesses of royalty, both domestic and foreign? Or were these cards sold as popular depictions of royalty, for ordinary people who were curious to know what their celebrities looked like?

This is something I’ve often wondered about, about this era: given that – for instance – manuscript illustrations range from extremely crude and generic to extremely accomplished and detailed, to what extent did common people (even the well-to-do ones amongst them) know what their rulers and other famous people looked like? How many of these popular depictions might there have been in circulation, in different ephemeral forms? It is through sheer luck that this deck of cards has survived, after all.

And the most fascinating idea of all: how many of such popular depictions might actually have survived, and be out there even as we speak – scattered all over Europe or beyond, still unidentified?